“The skulls of those two British Soldiers killed at the bridge”

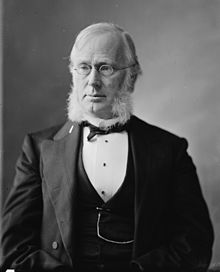

Stark became an American citizen but maintained ties with his native country, promoting immigration and friendly relations.

Like Isaiah Thomas, the Rev. Albert Tyler, Daniel Seagrave, and other men who took up studying and preserving history without a college education, Stark started out in the printing business. In his case, he mastered the new technology of electrotyping and ran the Photo-Electrotype Company of Boston.

In the late 1800s Stark published several guides to the British West Indies illustrated with photographs by himself and others.

He also published books on local history through his firm: Illustrated History of Boston Harbor (1880) and Antique Views of ye Towne of Boston (1882) both reproduced many historic images of the town.

Stark might have made the biggest splash with his thick book The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution, published in 1910. Coming at the end of the Colonial Revival, he challenged the accepted American view of the Loyalists as aristocrats and traitors, highlighting their complaints of being mistreated. For this, critics charged that Stark was a historical muckraker and a controversialist, and indeed he probably was.

Among the stories Stark examined was the tale of the two British soldiers’ skulls dug up by a phrenologist. In doing so, however, he spread misinformation about that tale.

This chapter of the story started in 1908 with a man named Albert Webb coming from Worcester, England, to Worcester, Massachusetts, on a sister city project. On 31 March 1909, Webb wrote to the Boston Transcript suggesting that someone should place a larger marker near the North Bridge in Concord, commemorating the two British soldiers killed and buried nearby with some lines by James Russell Lowell.

The editor of the Transcript wrote a response endorsing the idea but also insisting that the grave had been maintained with “old New England reverence.”

Stark replied with a letter to the newspaper’s “Notes and Queries” department asking:

1. Can anyone give the names of the two British soldiers killed at Concord Bridge, or inform me it there were any papers taken from their bodies that would identify them? I have been informed that there were.The only response to the newspaper was: “before the alleged action of the selectmen excites the Concord people, they should insist upon his producing adequate evidence.”

2. One of the soldiers was left wounded on the bridge; what was the name of the “young American that killed him with a hatchet”?

3. When did the selectmen of Concord give Professor Fowler permission to dig up the two bodies of the British soldiers and remove the skulls to be used for exhibition purposes?

But in The Loyalists of Massachusetts, Stark published this 12 April letter from Ellery B. Crane, librarian of the Worcester Society of Antiquity, as what he deemed adequate evidence:

Mr. Barton has handed your letter to me and I write to say that the skulls of those two British Soldiers killed at the bridge in Concord were once the property of this Society, we having purchased them of the Widow of Prof. Fowler, the phrenologist, who some years ago went about the country giving lectures and illustrating his subjects.This letter offers yet another version of our story, with two skulls returned to the grave in Concord. Otherwise, it accords with what Hoar wrote in his 1891 letter returning one skull, and with what people in Concord gossiped about according to an 1895 Boston Sunday Globe article.

Prof. Fowler got permission to dig up those skulls from the Selectmen of Concord, and he carried them about with him and used them in his lecturing. After his death one of the members learned of them and we purchased the skulls and they were in our museum some time.

The late Senator [George F.] Hoar learning that we had them, came to know if we would be willing to return them to Concord that they might be put back in the ground from whence they were taken. As he seemed quite anxious about it, consent was given, and they were sent to Concord to be placed in their original resting place. Presume they are there at the present time.

But that account doesn’t match what the Rev. Albert Tyler wrote out for the Worcester Society of Antiquity in 1905, in a paper read to members by none other than Ellery B. Crane. Nor what Crane had told society members during an excursion to Concord in April 1906. Both of those accounts had recently been printed in the society’s Proceedings, presumably under Crane’s direction.

Nor does the belief that the Worcester Society of Antiquity owned two British soldiers’ skulls match the intermittent newspaper accounts in the late 1800s about its display of a single skull.

Furthermore, Stark and Crane got the name of the phrenologist wrong. Orson Squire Fowler (1809–1887) and Lorenzo Niles Fowler (1810–1896) were prominent proponents of that new science in the mid-1800s. (Lest we think of the Fowler brothers as total loons who did nothing for American society, they also quietly paid Walt Whitman’s costs for printing the second edition of Leaves of Grass.) But all other sources are clear that the phrenologist who lectured with British soldiers’ skulls was Walton Felch.

Stark’s Loyalists of Massachusetts was widely distributed. It’s useful on some points of genealogy and real estate, notoriously misleading on others, such as the engraving of Paul Revere as a bearded rider with a coonskin cap and a pistol. Stark’s book and Ellen P. Chase’s Beginnings of the American Revolution, also published in 1910, appear to be the first books to print the name of Ammi White as the young man who killed a wounded soldier at the North Bridge.

A thick book, especially one in lots of local libraries for genealogists to consult, is harder to ignore than a gossipy newspaper story. The Loyalists of Massachusetts turned the tale of Concord’s selectmen letting a phrenologist make off with the two soldiers’ skulls into a long-lasting part of the town’s local lore.

Even though that lore was based on a mistake.

TOMORROW: Back to the disinterment.